Of Whiskey Flasks and Bathtub Gin

Wednesday, October 7, 2015 at 11:21AM

Wednesday, October 7, 2015 at 11:21AM by Doris Berdahl

Veteran local storyteller Swede Pedersen, who was born and raised here and had a rich treasure trove of memories of Sausalito from the 1930s on. This article, somewhat edited and abridged,is based on an interview that appeared in MarinsScope on February 8, 1972.

“When I was only 12 years old,” Pedersen recalls, “we used to go down to Shelter Cove at night, and when the fog came in we’d tunnel under the pilings of the old Walhalla, the German beer garden that’s now the Valhalla, where we knew a lot of the stuff was stored. I remember when I made my first sale to one of our leading citizens. He said, `You’ve done your civic duty by turning this in, young man. If you find anymore of these bottles, you just bring them straight to me’.”

The distinct class divisions that existed in Sausalito at that time apparently vanished when it came to the forbidden pleasures of whiskey flasks and bathtub gin. While the hill people were making fig wine in their basements, the young men of the working class were flirting with prison terms for the sake of the big money offered by men like “Baby Face” Nelson, who spent a brief time in Sausalito in the early 1930s.

By and large, the attitude among the otherwise law-abiding citizenry was a wink and a nod. From the stately homes of the Banana Belt to the proletarian flatlands, there was amused acquiescence -- or covert indulgence in guilty pleasures. “Baby Face” Nelson’s custom-built Duesenberg used to be brought into Rose’s Garage on Caledonia Street (now the Real Foods store), one old-timer recalled for this interview. “I’d wash and polish it, and I can still remember the bullet-proof windshield and the secret compartment under the seats where the booze was kept.”

“Sometimes we’d get together at the Women’s Club,” remembered a “hill lady” who didn’t care to be identified. “Our local pharmacist would mix up some of his medicinal alcohol with a few juniper leaves, and we’d have a little gin party.”

According to Pedersen, a local Boy Scout troop was sometimes “chaperoned” by men posing as troop leaders who took the boys to a lonely West Marin beach, settled them around a bonfire, treated them to a wiener roast and encouraged them to sing camp songs at the top of their lungs. In the meantime, the chaperones loaded up a long, black limousine down by the water with contraband brought in by boat.

The prevalence of crude stills in private homes seems to have approached the

proportions of a cottage industry. But since big money was often at stake, the fun and games of local law breaking inevitably came to be overshadowed by the deadly serious operations of big-time gangsters. “There were more unidentified bodies found floating in the bay and laying in the back roads during that period than at any other time in the history of this area,” said Pedersen. “Our Boys Club, who sponsored the Sausalito Bears ball club, held whist parties to pay for our uniforms. Our headquarters were in the basement of a house on Spring Street where a speakeasy operated on the upper floors. So it didn’t surprise us when we found a machine gun dismantled and cleaned one day out in our horseshoe throwing pit.”

In addition to a liberal social climate, there were also fortuitous geographical reasons for a widespread flouting of the dry laws in Marin and Sonoma counties. “Because of all the inlets up and down the coast west of here,” Pedersen pointed out, “there were plenty of chances for small, fast boats, carrying contraband from Canadian and Mexican ‘mother ships’ laying offshore in international waters, to come in and unload their cargo on the beaches.”

In the days before the Golden Gate Bridge was built, Sausalito was known among rumrunners as “the bottleneck” through which illegal liquor had to be funneled to San Francisco’s speakeasies. They had to make it through downtown and onto a San Francisco-bound ferry without detection. Pedersen told of how bootleggers would meet at the old Caesar’s Inn on Tocoloma Road, near Inverness, and make plans for a shipment to the city.

“A call would go out to a trusted telephone operator in San Rafael – often a girlfriend of one of the men – who would relay the message to Sausalito that everyone should be off the streets because a truckload was coming through. The truck, covered with a tarpaulin, would time the run so that it could catch the last ferry of the night within seconds before it left, and that way keep a jump ahead of the federal inspectors.”

Obviously, in order for such an operation to run smoothly, almost everyone in Sausalito had to be an accessory to the fact, either actively or passively. There were only two policemen on the force then, plus a night watchman. The degree to which they looked the other way can only be a matter of conjecture today.

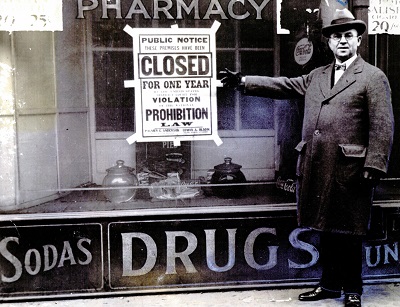

The wages of sin: A local pharmacy was shut down for violating Prohibition laws in the 1920s.

Photo courtesy of Sausalito Historical Society

Reader Comments