Cimba and the Farallon Patrol

Wednesday, October 14, 2015 at 03:00PM

Wednesday, October 14, 2015 at 03:00PM The following story has been condensed from an article published in the Marin Scope in March 1981.

by Annie Sutter

It's 6:15 a.m., the sky's a chilly, mottled, sullen pinkish-gray, and I'm tiptoeing through patches of frost on an uninviting expanse of dock leading out to the berth where Cimba, the 32' Grand Banks, awaits the arrival of the week's Farallon Patrol. Soon all the shivering members of the expedition have gathered -- Charlie Merrill, skipper, bustling about loading gear, groceries and rolls of chicken wire; two members of the Point Reyes Bird Observatory (from here on known as the PRBO) who will relieve other scientists studying bird and seal populations at the windswept islands, and others doubtless wondering why they're casting off into a leaden and chilly sea with a rough day ahead.

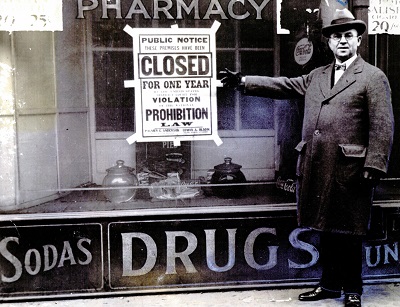

Cimba cruising off Sausalito

Photo courtesy of S.F. Bau Adventures.

At 7 a.m., coffee, croissants and a glorious display of pink, gold, and orange sunrise have done a great deal to dispel the cold and gloom as Cimba joins the early morning parade of fishboats and assorted craft heading out the Gate for a crack at salmon, albacore and cod. Cimba's engine purrs happily as she heads out into what has become a morning sparkly sea of silver and blue and long, low smooth swells -- maybe no one will be seasick this run! A caravan of cormorants heads out to sea in tight formation and flocks of murres disappear beneath the waves to port, and reappear in unison, yards away to starboard. An hour later, the swells have increased in volume, the wind has freshened, and the sparkly sea, stirred up into mean little khaki colored choplets, begins to slap and break over the bow while Cimba leaps through the swells, digs down, and rides up, shaking off spray.

By 11 a.m. the islands, at first smoky blobs on the horizon, have been taking shape for the past couple of hours. They consist of three rocky, mainly barren and windswept groups; and the largest at 90 acres with a lighthouse on top is Southeast Farallon, home of the PRBO and our destination. We've made radio contact with the island, and people are waiting up on a large concrete landing with a crane. We've got an easterly wind, the worst kind for the pick-up, and the swells are just about big enough to call off the rendezvous -- but not quite. They radio to come on in and tie up to a big seaweed-encrusted buoy, which is rolling violently, tugging at its mooring.

A Boston Whaler with two people in it is hanging off the crane and being lowered slowly into the water, a distance of about 25'. As it hits the water, the people's heads vanish behind swells, then reappear, and as the boat is unhooked from the hoist, it skitters off, bounding through the troughs, appearing and disappearing. Soon, a large box is dangling from the hoist, and the Whaler goes back to pick it up. It sways and lurches while the boat dances below; then, as the two finally meet, the box is deftly unhooked and it lands with a plop in the Whaler, which backs off quickly and heads out to Cimba to unload. Back and forth they go - box returned empty, box hoisted, box reloaded, box returned to Cimba filled with equipment, duffel bags, packs and luggage of those who will be leaving.

When it's time for the staff to disembark from the landing at the top of the cliff, a new conveyance is hooked onto the crane - a scary looking thing called a "Billypugh", developed for use on big oil rigs. The people climb onto the top, cling to it as it's lowered, swaying, to the Whaler. They say it's a lot easier to get on at the top than off at the bottom. Soon we have four new faces aboard, four sets of belongings, and four people who say they are glad to be going home. We unleash Cimba from the rolling buoy, and head back into the chop and the swells, for the Golden Gate.

After reading about sharks and tumultuous seas in Cimba's logbook, I look around apprehensively, but today the sea is kind, and the boat is faithfully buzzing along toward home. By 5 p.m., we're nearing the Gate, bucking a fierce ebb tide, but making headway. It's dark by the time the amber overheard lights of the bridge have been left behind, and as we approach Sausalito traffic scurries along Bridgeway, and the lights twinkle up in the hills. Cimba glides into her berth, veteran of another Farallon Patrol voyage. "Piece of cake!" says Charlie.

Charles H. Merrill, a small boat sailor and a pillar of the Sausalito community, died in his hillside home overlooking San Francisco Bay at age 95. In 1990, Cimba went into disrepair and in 1999, Charlie Merrill decided to sell her to Capt. Paul Dines of SF Bay Adventures, which offers private charters on her for up to 6 guests. For more information, visit sfbayadventures.com.